He Went Deep

Reggie, Reggie.

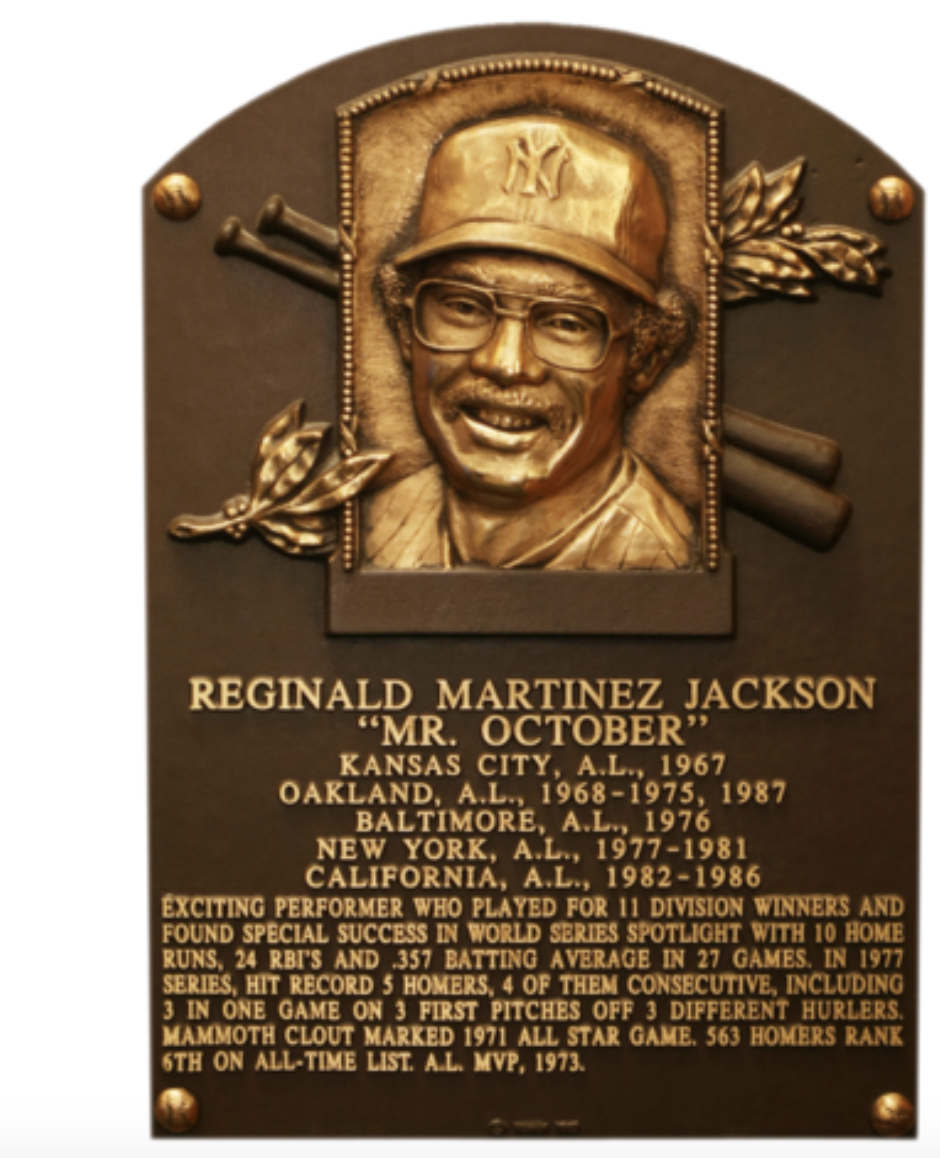

Say it loud, and it’s almost like chanting. And we should raise our voices, along with our glasses, on May 18, to celebrate the 75th birthday of Reginald Martinez Jackson. Here’s to Mr. October. Here’s to a 14-time All-Star, a two-time World Series MVP, the 1973 American League MVP, the No. 5 home run hitter of all-time (563) when he retired in 1987, the most pro-whiffic hitter in history (2597) and a Hall of Famer upon his election on January 5, 1993. Here’s to a former college football hero, a movie star, a candy bar, a broadcaster, a distant cousin of Barry Bonds, a pioneer in facial hair and “the straw that stirs the drink.”

Reggie, Reggie.

Say it softly, and it conveys amazement on one side of the comma, and amusement on the other. A smile, a shake of the head. He was a work of art and a piece of work. He was a walking paradox. For someone who was larger than life, he was surprisingly small in stature.

He loved the attention yet valued his privacy. He was considerate and contemplative, but he could also be tempestuous and cruel. He wasn’t just a hot dog. He was the 1,996-foot wiener that Sara Lee made for the 1996 Summer Games in Atlanta. As teammate Darold Knowles once said, “There isn’t enough mustard in the world to cover Reggie Jackson.”

There’s only so much room on a Hall of Fame plaque.

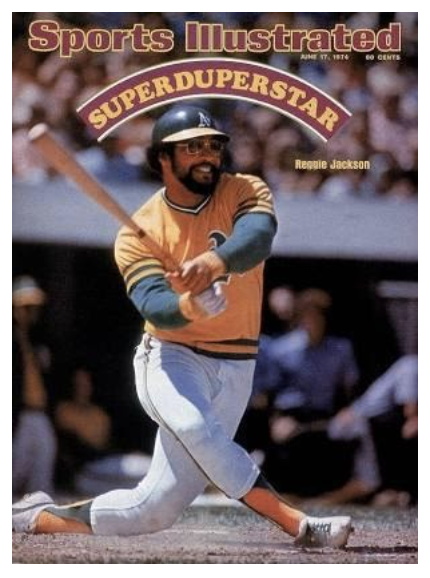

For 21 seasons and 11 postseasons, there weren’t enough reporters in the press box to cover him, either. He was as much a blast to write about as that home run he hit off Dock Ellis in the ’71 All-Star Game, the one that hit the transformer on the roof of Tiger Stadium. Before I get around to my Reggie story, I want to resurrect the lead from Roy Blount Jr.’s classic profile of Reggie in the June 17, 1974 issue of Sports Illustrated:

“The nearly empty clubhouse of the world champion Oakland A’s looks like the men’s room of an old, disreputable movie theater, except that Reginald Martinez Jackson, a superstar advancing toward superduperstar status, is naked in it, taking his naturally beautiful left-handed stance and a swinging a 35-inch, 37-ounce flame-treated bat, intensely, reflectively.

“Whupp. Whupp. Even though he is cutting through thin air he seems to be making good contact.”

The man sold a lot of copies.

I urge you to read the whole piece: https://vault.si.com/vault/1974/06/17/everyone-is-helpless-and-in-awe. But if you don’t, take this quote from Reggie away from it, his stated desire to join the game’s truly elite: “Tom Seaver. Pete Rose. Frank Robinson. Henry Aaron. Jim Palmer… These guys are living human definitions of the word determination. They walk on the field and you sense it. They buy an ice-cream cone and you sense it. They can go to a movie and stand out in the crowd with the lights out.”

He got that wish… and more. Let’s put it this very unscientific way: Reggie’s Wikipedia entry runs to 22 pages. Among the players he mentioned, only Aaron’s is longer. He had the heart to overcome a devastating football injury in high school, and he was at the heart of two of the greatest teams in baseball history: The Mustache Gang of the Oakland A’s, who won five straight division titles and three consecutive world championships (1972-74) and the Bronx Zoo that gave the Yankees four AL East titles and two straight world championships (1977-78).

He also had the balls to challenge owners (Charles Finley, George Steinbrenner), managers (Dick Williams, Billy Martin), teammates (Billy North, Thurman Munson) and fate itself. He couldn’t stay out of trouble. But he also thrived in the biggest moments.

Take the 1977 season. Steinbrenner had signed Jackson to a huge, five-year deal ($2.96 million) deal in the offseason, but at a bar that spring, he told the Sport magazine writer who was profiling him, “I’m the straw that stirs the drink. Maybe I should say me and Munson, but he can only stir it bad.”

When that hit the newsstands, the shit hit the fan. Then on June 18 in Boston, he half-heartedly fielded a ball in right, and Martin pulled him from the game. The viewers in the nationally-televised game then saw Martin and Jackson nearly come to blows in the dugout—coaches and former backstops Yogi Berra and Elston Howard had to separate them.

Cut to October 18, four months later, and Reggie is being mobbed in the Yankee dugout after hitting his third homer of World Series Game 6 to give the Yankees an 8-3 lead over the Dodgers. (They won 8-4 to clinch the Series.) “Look at the beam on his face,” said ABC’s Howard Cosell. “How can you blame him? He’s answered the whole world.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZNTzxVNv24

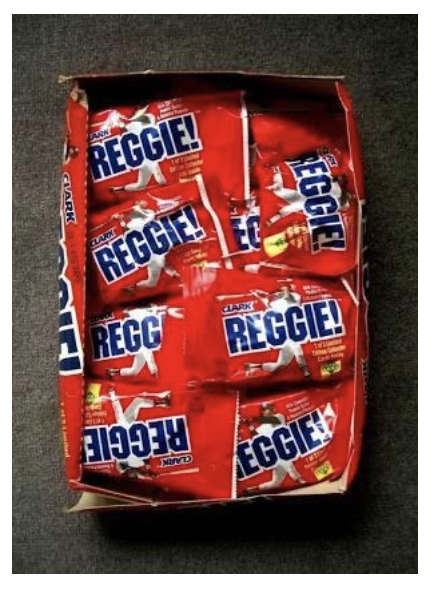

Those two snow globes, the fight in the dugout and the reception in the dugout, represent a career that was marred by incidents and marked by heroics. There was always something. In 1976, when he was rented by the Orioles for a year, he complained that if he played in New York, “They would name a candy bar after me”—his way of comparing himself to Babe Ruth.

Well, Standard Brands did just that and handed out Reggie! bars to the fans before the Yankees’ home opener in 1978. When he jogged out to right field after hitting a home run, the game had to be stopped because the fans had thrown so many of the candy bars onto the field.

Even before the candy bar, he was a sweet swinger.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLO62LkosDI

I wasn’t yet covering baseball for SI when the candy came raining down, but I was there for a similar show of affection three years later in Comiskey Park. Reggie had been struggling—so much so that Steinbrenner had ordered him to take a series of medical tests. So I went out to Chicago to take his temperature. In the late innings of a Friday night game, he broke out of his slump with a single, then tagged up on a long fly ball and took second base. The White Sox fans were so appreciative of his hustle that they began throwing money at a man who made $600,000 a year. What’s more, Reggie eagerly picked up the loose change. His take was $31.27 and one phone number.

In the cab ride back to his hotel, he told me, “Wasn’t that something? I had such fun tonight. It was wonderful. They said, ‘He’s down, but he’s busting his ass.’ People know I’m getting jacked around. Things like that—they’re better than beer. It was a real show of love, or at least a show of like.”

Then he said, “That’s just part of the roller-coaster ride that’s Reggie Jackson. Wherever you go in the world—Denmark, China, Australia—they may not have heard of the Golden Gate Bridge or Mardi Gras, but they’ve heard of the New York Yankees. It’s a privilege to wear the uniform.”

Yes, he talked like that. You couldn’t scribble fast enough, partly because you were wasting energy by smiling at your luck. There was nobody better at the dance between athletes and sportswriters than Reggie. He knew what you wanted, and he knew how to give as well as he got. I once heard him tell an overweight baseball writer who had approached him, “Hey, Charlie, mix in a salad.”

The Yankees let him play out his contract and he signed with the Angels. Upon his return to Yankee Stadium on April 27, 1982, he heard the fans chant, “Steinbrenner Sucks!” as he approached the plate, whereupon he homered off Ron Guidry. He had a damn fine season, hitting 39 homers with 101 RBIs as the Angels won their division. But he became a full-time DH in ’83 and slumped badly (.194)—some blamed the lack of adulation he usually got in right field, some blamed the distraction of working on an autobiography with Mike Lupica.

Whatever the case, he came to camp in ’84 10 pounds lighter. “I didn’t just go in for a tune-up,” he said. “I went in for a total overhaul, engine, style, the works.” And he started hitting again, which is why SI dispatched me to write about the new/old Reggie Jackson. The problem was that he had stopped talking to the press. When I told him of my assignment, he said, “Steve, don’t worry. I think of you guys from Sports Illustrated as my beat guys.”

He had to go to Hartford the next day for a car commercial, so we sat in the back of a limo and chatted. At one point he said to me, “If I was a car, I wouldn’t be a Rolls-Royce. No. I’d be like an L-88 Corvette. Nineteen sixty-seven. That’s the last year of the true Sting Ray. Five hundred and sixty horsepower. Four-speed. No fuss, no muss, no radio, no heater. Only takes 103-octane gasoline. They don’t make them like that anymore.”

No, they don’t.

-30-